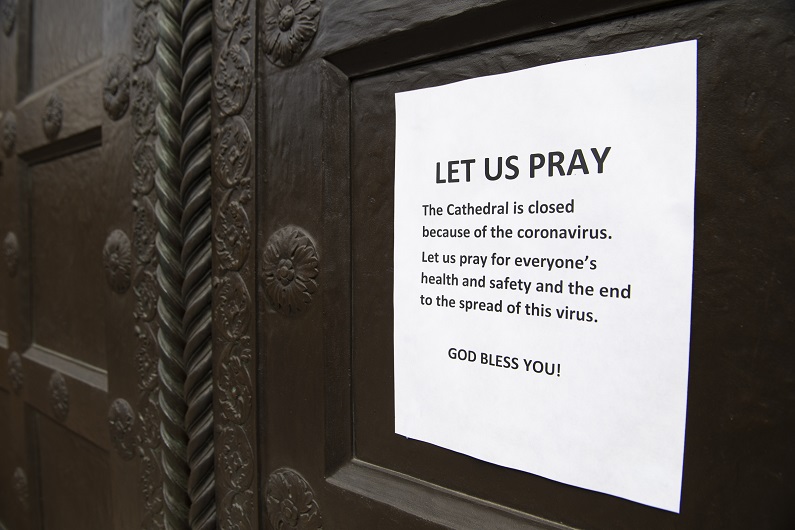

The coronavirus pandemic has caused disruption around the world. To politics, economics, and to the life of the Church: most especially to the steady regularity of her sacramental life, which many Catholics see as the anchor of consistency amid a world of chaos.

“Stat crux dum volvitur orbis,” the Carthusians say— The cross is steady while the world turns.

But while the cross remains steady, restrictions on public liturgies and access to church buildings have made the sacramental life of the Church less visible to most Catholics, and less available.

The guidance of the Holy See has served as the framework for many liturgical restrictions: the Vatican announced its cancellation of public Holy Week liturgies before the Italian government could try to impose it, and signalled to local ordinaries that they could do the same.

The Holy See has also issued instructions on how to modify certain sacramental celebrations, among them the sacrament of penance, in light of the global effort to slow the spread of the coronavirus pandemic.

But in the U.S., some bishops have announced policies that extend beyond the guidance of the Holy See, and have left canonical experts, and some clerics, wondering about their legality.

It is unclear when, and if, the Holy See will step in with additional guidance, or issue judgments about the canonical legitimacy of some diocesan policies.

In some U.S. dioceses, bishops have told priests they are barred from hearing confessions or baptizing except in cases of “extreme emergency.”

On Wednesday, the Archdiocese of Newark circulated a memo to “all serving in the archdiocese” reiterating various policies already in force and issuing new directives. Among the new policies, vicar general Monsignor Thomas Nydegger announced that “the Sacrament of Reconciliation is suspended until further notice with the exception of an extreme emergency.”

On Thursday, spokesperson for the Archdiocese of Newark told CNA that “an ‘extreme emergency’ is understood to be ‘danger of death,’ in pericolo mortis, in canonical legislation.”

“Danger of death” is a technical canonical term, referring to the proximate danger of death from a particular cause. In that technical sense, “danger of death” does not include a generalized fear of danger of death, even if well founded.

Restriction of the sacrament of confession to “emergency cases,” especially if such cases are understood to refer only to “danger of death” in the technical sense, is an effective blanket ban on access to the sacrament for most Catholics, most the time- even while the right to the sacrament is enshrined in canon law.

Canon 843 §1 of the Code of Canon Law states that “The sacred ministers cannot refuse the sacraments to those who ask for them at appropriate times, are properly disposed, and are not prohibited by law from receiving them.”

Canon 988 §1 requires that “A member of the Christian faithful is obliged to confess in kind and in number all serious sins committed after baptism.” While the minimum requirement of the law is for all Catholics to confess at least once a year, the Church recommends the season of Lent as a special time for confession in preparation for Easter.

The website of the U.S. bishops’ conference explains that “it is necessary to confess one’s mortal sins to a priest in the Sacrament of Penance in order to receive forgiveness from God.”

Beyond the restriction of confession, other diocesan norms have raised questions about canonical legitimacy.

The Archdiocese of Kansas City last week conveyed to priests that cell phones can be used during sacramental confession, as long as both priest and penitent can see one another during the call. The archdiocese even suggested that priests use a Google Voice number in order to avoid distributing their cell phone numbers.

The archdiocese declined to comment to CNA about the suggestion, and especially about the privacy concerns that the use of the Google Voice platform, or an unsecured cell phone, might represent for a sacrament ordinarily offered in strictest secrecy.

But whether the archdiocesan policy is canonically permitted is, at the moment, ambiguous. A Peruvian bishop last week rescinded a permission he’d granted for confession-by-phone, because, he said, it was not clear to him that the Holy See would permit such a thing, even if it were sacramentally possible.

Clarity on the question, especially as more dioceses face “shelter in place” orders seems likely to become immediate for many priests.

In at least one U.S. diocese, the Archdiocese of Chicago, priests have been told that during the pandemic, the emergency celebration of baptism requires the permission of the bishop— despite canonical norms permitting anyone, even a layperson, to celebrate baptism in a true emergency, in which, presumably, an ordinary minister of baptism can not be quickly reached.

At the moment, it is unclear how much authority various diocesan restrictions- on both the ministers of the sacraments and their would-be recipients- actually carry. The policies seem to be, at the very least, praeter legem, beyond the law.

To be sure, some bishops would contend that these restrictions are regrettable but necessary to save lives and halt the spread of disease.

The threat of the pandemic to human life is so immediate, they would argue, that extraordinary measures are necessary – even to the point of denying the faithful their right to the sacrament of mercy.

On the other hand, this argument rests on the immediate nature of the public health emergency, which itself seems to contradict the new restrictions.

The premise that the danger of death is real and universal creates a rational feedback loop. For example, the same extreme circumstances said to justify sweeping limits on priests hearing confessions at the same time triggers the Church’s de iure permission and duty for all priests, even laicised ones, to hear confessions and absolve sins.

Meting out what is, and is not, permissible is likely to become an urgent priority for the Vatican’s canonical and sacramental offices – it may be already. While the fog of war, so to speak, has mostly shrouded decisions in the early months of the global pandemic, if the status quo continues, hard questions from Catholics are going to require clear answers.

Canonists will likely insist that the law already provides for most emergency circumstances, and that making new policies on the fly, in the middle of a crisis, is rarely a good idea. But public health officials and others are likely to push for ongoing stringent measures, and with good reason.

While it seems quite clear that bishops worldwide are acting in good faith to respond to a crisis, eventually they too will want definitive norms upon which to hang local policies.

Universal law – and the universal legislator, Pope Francis – is likely to soon face calls from those bishops for a systematic treatment of those questions- especially if members of various bishops’ conferences find themselves locked in disagreement.

While the Vatican has issued some policies, Pope Francis has also warned in recent days that “Drastic measures are not always good.”

“May the Lord give [pastors] the strength and also the ability to choose the best means to help,” the pope said at the beginning of Mass March 13.

“Let’s pray for this, that the Holy Spirit may give to pastors the ability for pastoral discernment so that they might provide measures which do not leave the holy, faithful people of God alone, and so that the people of God will feel accompanied by their pastors, comforted by the Word of God, by the sacraments, and by prayer.”

While no serious canonists question the bishop’s right – even prudence – to suspend the public celebration of the Mass during an emergency, the liceity of other suspensions is decidedly less clear. Amid the various unforeseen and unexpected challenges of a global pandemic remains the salvation of souls – the supreme law of the Church.