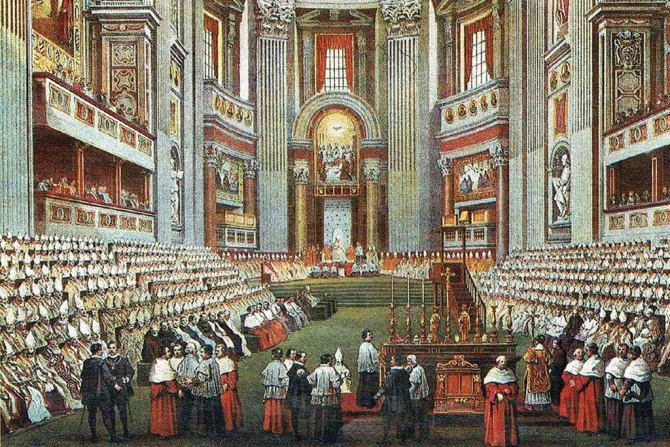

A contemporary depiction of the First Vatican Council. | public domain

The First Vatican Council, held in 1869 and 1870 and left unfinished due to the capture of Rome, is regarded as the forerunner of Vatican II and is best known for its definition of papal infallibility.

The historian Father Philip Hughes wrote of Vatican I as “the most striking evidence … as to the Church’s essential independence of all but the grace of her divine Founder and her divine Guide.”

Vatican I’s context was the upheaval of the French Revolution, as the product of the enlightenment, and the subsequent liberalism of the 19th century. It was called by Blessed Pius IX.

The council produced two documents: Dei Filius, a dogmatic constitution on the Catholic faith, and Pastor aeternus, a first dogmatic constitution of the Church of Christ.

Dei Filius

Dei Filius affirmed the value of reason and its rights in the realm of religion, teaching, for example, that God can be known with certitude by the natural light of human reason from created things.

The constitution on the faith also declared that “the books of the Old and New Testament, whole with all their parts,” just as they were enumerated by the Council of Trent, “are contained in the older Vulgate Latin edition, and are to be accepted as sacred and canonical.” It added that no one is permitted to interpret Scripture itself contrary to the sense which Holy Mother Church has held and holds, “or even contrary to the unanimous agreement of the Fathers.”

In addition, Dei Filius discussed the definition of faith; its relation to reason, which cannot be one of opposition; and the just freedom of science.

Pastor aeternus

It was the dogmatic constitution of the Church of Christ that defined papal infallibility and the universal primacy of the Roman Pontiff.

Pastor aeternus taught that with respect to the pope’s immediate episcopal jurisdiction, the pastors and faithful of whatever rite and dignity “are bound by the duty of hierarchical subordination and true obedience, not only in things which pertain to faith and morals but also in those which pertain to the discipline and government of the Church.”

It added that this papal power “is so far from interfering with that power of ordinary and immediate episcopal jurisdiction by which the bishops … have succeeded to the place of the apostles, as true shepherds individually feed and rule the individual flocks assigned to them, that the same is asserted, confirmed, and vindicated by the supreme and universal shepherd, according to the statement of Gregory the Great: ‘My honour is the universal honour of the Church. My honour is the solid vigour of my brothers. Then am I truly honoured when the honour due to each and everyone is not denied.’”

Arguing for papal infallibility, Pastor aeternus stated that “the Holy Spirit was not promised to the successors of Peter that by His revelation they might disclose new doctrine, but that by His help they might guard sacredly the revelation transmitted through the apostles and the deposit of faith, and might faithfully set it forth.”

The council then taught that it has been divinely revealed: “that the Roman Pontiff, when he speaks ex cathedra, that is, when carrying out the duty of the pastor and teacher of all Christians in accord with his supreme apostolic authority he explains a doctrine of faith or morals to be held by the universal Church, through the divine assistance promised him in blessed Peter, operates with that infallibility with which the divine Redeemer wished that His Church be endowed in defining doctrine in faith and morals; and so such definitions of the Roman Pontiff from themselves, but not from the consensus of the Church, are irreformable.”

The prospect of the definition of papal infallibility had not been universally welcomed, with some believing the act of definition to be inopportune.

The definition of infallibility led to the formation of the Old Catholic Church, with some Catholics from Germany, Switzerland, and the Netherlands going into schism, though no Catholic bishops joined them.

St. John Henry Newman and the council

St. John Henry Newman was concerned about the prospect of the definition, though once it was adopted, he welcomed its moderation and the limits it placed on papal infallibility.

In his 1875 Letter to the Duke of Norfolk, Newman wrote that in the act of definition, “the principle of doctrinal development, and that of authority” had “never in the proceedings of the Church been so freely and largely used,” while denying that “the testimony of history was repudiated or perverted.”

He added that “the long history of the contest for and against the pope’s infallibility” had been a “growing insight through centuries … ending at length by the Church’s definitive recognition of the doctrine thus gradually manifested to her.”

Newman noted that “Papal and Synodal definitions, obligatory on our faith, are of rare occurrence; and this is confessed by all sober theologians.”

“There is no real increase” in the pope’s authority, Newman wrote, for “he has for centuries upon centuries had and used that authority, which the definition now declares ever to have belonged to him.”

Germany and the council

In Germany, the definition precipitated the Kulturkampf, a conflict between Otto von Bismarck’s government and the Church over the state’s role in ecclesial appointments; Bismarck held that the definition had made an absolute monarch of the pope, with bishops his mere delegates.

Germany’s bishops responded to this charge in a joint declaration of 1875, saying that “the decrees of the Vatican Council give not even the shadow of a foundation to the assertion that the pope has been made by them an absolute ruler … even as far as concerns ecclesiastical matters, the pope cannot be called an absolute monarch, since he is subject to Divine Law and is bound to those things which Christ set in order for His Church. He cannot change the constitution of the Church which was given to it by its Divine Founder.”

They added that “it is in virtue of the same divine institution upon which the papacy rests that the episcopate also exists. It, too, has its rights and duties, because of the ordinance of God himself, and the Pope has neither the right nor the power to change them … According to the constant teaching of the Catholic Church, expressly declared at the Vatican Council itself, the bishops are not mere tools of the Pope.”

Blessed Pius IX confirmed that year the German bishops’ explanation of the teaching of Vatican I, writing that “it ought to provide the occasion for our most fulsome congratulations; unless the crafty voice of some journals were to demand from us an even weightier testimony — a voice which, in order to restore the force of the letter which has been refuted by you, has tried to deprive your hard work of credibility by arguing that the teaching of the conciliar definitions approved by you has been softened and on that account does not truly correspond with the mind of this Apostolic See.”

“We, therefore, reject this sly and calumnious insinuation and suggestion; since your declaration expresses the inherent catholic judgement, which is accordingly that of the sacred Council and of this Holy See, skilfully fortified and cleverly explained with such brilliant and inescapable arguments that it can demonstrate to any honest person that there is nothing in the attacked definitions which is new or makes any change,” the pope wrote.

The German bishops’ declaration was cited by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in its 1998 Considerations on the Primacy of the Successor of Peter in the mystery of the Church, where it wrote that the Roman Pontiff “does not make arbitrary decisions, but is spokesman for the will of the Lord, who speaks to man in the Scriptures lived and interpreted by Tradition; in other words, the episkope of the primacy has limits set by divine law and by the Church’s divine, inviolable constitution found in Revelation. The Successor of Peter is the rock which guarantees a rigorous fidelity to the Word of God against arbitrariness and conformism: hence the martyrological nature of his primacy.”

In “The Spirit of the Liturgy” in 2000, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger wrote similarly, “the First Vatican Council had in no way defined the pope as an absolute monarch. On the contrary, it presented him as the guarantor of obedience to the revealed Word. The pope’s authority is bound to the Tradition of faith.”

The end of the council and Vatican II

The First Vatican Council was suspended in 1870 when troops of the Second French Empire, who were guarding Rome from the advancing Kingdom of Italy, withdrew from Rome upon the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War.

The Kingdom of Italy occupied Rome, the Papal States were disestablished, and Blessed Pius IX became the “prisoner of the Vatican.”

The council had been meant to treat of the Church as both a perfect society and as the mystical body of Christ. The capture of Rome precluded further discussion of the Church beyond the role of the Roman Pontiff.

The themes that were to have been taken up were elaborated by subsequent popes, and at the Second Vatican Council, especially in Lumen gentium, its dogmatic constitution on the Church.

The CDF wrote in 1998 that “The Second Vatican Council, in turn, reaffirmed and completed the teaching of Vatican I, addressing primarily the theme of its purpose, with particular attention to the mystery of the Church as Corpus Ecclesiarum. This consideration allowed for a clearer exposition of how the primatial office of the Bishop of Rome and the office of the other bishops are not in opposition but in fundamental and essential harmony.”

Vatican II complemented the First Vatican Council’s teaching by treating more fully of the College of Bishops, the nature of the episcopacy, and episcopal collegiality.

Source: CNA