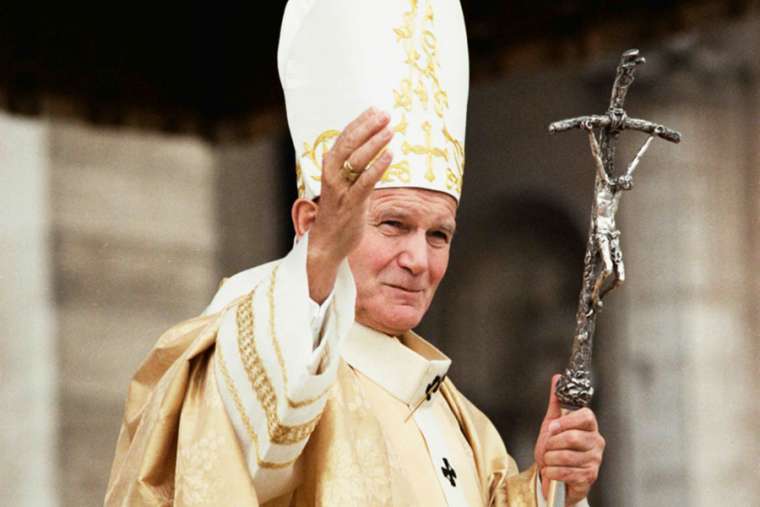

Pope St. John Paul II. Credit: L’Osservatore Romano

Pope St. John Paul II— who would have turned 100 years old May 18— was a man of great humility, whose nearly 27-year pontificate nevertheless left a lasting impression on the Catholic Church and the world, according to his biographer and others who knew the man.

“He’s the great Christian witness of our time. He’s the exemplar of the fact that a life wholly dedicated to Jesus Christ and the Gospel is the most exciting human life possible,” George Weigel, the pope’s biographer, told CNA.

After an upbringing marked by the sadness of losing his mother, father, and brother, he endured the Nazi’s occupation of Poland, working hard as a laborer and eventually clandestinely studied for the priesthood and became cardinal archbishop of Krakow.

He eventually became the most traveled pope in history, and a beloved saint. He died in 2005, and Pope Francis canonized him in 2014.

“This man lived a life of such extraordinary drama that no Hollywood scriptwriter would dare come up with such a storyline. It would just be regarded as absurd,” Weigel added.

Weigel— and a former member of the Swiss Guard who served John Paul II for four years— spoke to CNA about what they think the pope will be remembered for in the next 100— or even the next 1,000— years.

The making of a saint

Karol Wojtyla was born a century ago, on May 18, 1920 in Wadowice, Poland.

His father, also named Karol, was a Polish Army lieutenant, and his mother Emilia was a school teacher. The couple had three children: Edmund in 1906; Olga, who died shortly after her birth; and Karol, named for his faither, in 1920.

Karol was bright; a good student and an aspiring actor. Upon graduating from high school, he enrolled in Krakow’s Jagiellonian University and in a school for drama in 1938.

The Nazi occupation forces in Poland closed the university in 1939, and young Karol had to work in a quarry for four years, and then in the Solvay chemical factory to earn his living and to avoid being deported to Germany.

To make matters worse, Karol would lose his entire immediate family while still a young man. His mother died in 1929; his older brother Edmund, a doctor, died in 1932; and his father died in 1941.

In 1942, aware of his call to the priesthood, he began courses in the clandestine seminary of Krakow, run by Cardinal Adam Stefan Sapieha, archbishop of Krakow.

After the Second World War, he continued his studies in the major seminary of Krakow once it had reopened, and in the faculty of theology of the Jagiellonian University. He was ordained to the priesthood in Krakow on November 1, 1946.

On January 13, 1964, Pope Paul VI appointed him archbishop of Krakow, and later a cardinal on June 26, 1967.

Elected in 1978, he was the first non-Italian pope in 455 years.

Man of prayer

John Paul II was a man of deep prayer who loved and trusted God, and also had a deep devotion to Mary. The rosary was one of his favorite prayers, and he even gave the Church a new way to contemplate truths about Jesus in the form of the Luminous Mysteries of the Rosary,

Mario Enzler, a former Swiss Guard member who served John Paul II, said he hopes that people will remember the pope’s simplicity— a quality he was privileged to observe firsthand.

Enzler, now a professor and author of the book “I Served a Saint,” recounts the first time he ever met John Paul II, in 1989. It was very soon after he started as a Swiss Guard, on the third floor of the apostolic palace. He got a call saying the Holy Father was leaving his apartment to go to the Secretary of State’s office.

The protocol for the guards in that instance was to make sure nobody was milling around in the corridor, and to stand at attention as the pope walked by. Sometimes the pope would stop to talk to the guards— but oftentimes not.

In this case, when John Paul walked by, he stopped, and Enzler remained at attention.

“He said to me: ‘You must be a new one,’” Enzler recalled. He introduced himself.

“He let me finish my sentence, shook my hand…then he grabbed his hand with both of his hands, and said: ‘Thank you Mario, for serving who serves.’ Then he left,” Enzler said.

“The concept of servant leadership got, can I say, tattooed on my soul,” he remembers.

“Because he didn’t even know who I was, he saw that I was a new one, and he was kind enough to stop, shake my hand, ask my name; but he said, thank you for serving who serves.’

“The first time that I met him, I was obviously extremely emotional. I was really emotional when he came. I could sense he was special— he had something different.”

Enzler says he encounters many young people today who do not really know the beloved pope.

“He was a genius, a man of prayer…but he could make anybody feel comfortable. Doesn’t matter if he was talking to a Nobel prize [winner] or a homeless person, from the president of a state to a kindergarten schoolteacher,” Enzler said.

“He was capable of making everybody feel comfortable…it was just with a gesture, a caress, with a word, or just with a hug or just simply looking. I would say that in 1,000 years, he will be remembered because of his simplicity.”

Engagement with the world

Weigel, author of the definitive biography of John Paul II, for decades chronicled the pope’s engagement with civic leaders, and the way he influenced the political landscape he inhabited.

The pope famously met with dozens of political figures, in the course of 38 official visits, 738 audiences and meetings held with Heads of State, including with President Ronald Reagan— just a few days before Reagan called on Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down” the Berlin Wall.

“He thought of himself as the universal pastor of the Catholic Church, dealing with sovereign political actors who were as subject to the universal moral law as anybody else. I think he also had a very shrewd sense of political possibility,” Weigel said.

“He was willing to be a risk-taker, but he also appreciated that prudence is the greatest of political virtues. And I think he was quite respected by world political leaders because of his transparent integrity. His essential attitude toward these men and women was: how can I help you? What can I do to help?”

Despite his political shrewdness, John Paul II understood his role as primarily a spiritual, rather than political, leader.

This is especially evident, Weigel says, when one looks back on the saint’s speeches in his native Poland during his 1979 visit— one of the first visits outside Italy he made as pope.

“It’s not that he didn’t talk about politics primarily, he didn’t talk about politics at all,” Weigel said.

“Aside from acknowledging the presence of government officials on his arrival in Warsaw on June 2, and acknowledging their presence at his departure from Krakow on June 10th, he simply ignored them.”

The country was then under Communist rule. Catholicism was a centerpiece of Polish culture, as it had been for centuries, despite the Communists’ efforts to stamp it out.

“He spoke to his people about Polish culture, about what made Poland Poland. And at the center of that, of course, in addition to a distinctive history, and distinctive language, distinctive literature— the intensity of Poland’s Catholic faith.”

The pope’s primary impact on the world of affairs, Weigel says, was his central role in creating the revolution of conscience which made possible the nonviolent revolution of 1989 and the collapse of Communism in Central and Eastern Europe.

John Paul II had a remarkable capacity to encourage, Weigel said— in the sense of stirring up the courage that is within everybody.

“He embodied the cardinal virtue of courage, which we sometimes call fortitude. And that was faith-based,” he said.

“That was rooted in an absolute conviction that because God the Father had raised Jesus of Nazareth from the dead, and constituted him as Lord and Savior, God was going to get eventually what God wanted in history. And our task is not to imagine that we’re going to determine the final outcome of history.”

After John Paul’s visit to his native Poland in 1979, it would be another decade before the Solidarity Party in Poland, with the pope’s encouragement, would finally gain a majority in Parliament, and, largely peacefully, the country would shrug off the shackles of Communism.

Weigel says he believed European Communism would have collapsed at some point of its own “implausibility”— the system was so contradictory to the essential nature of the human person, he said, that it was bound to collapse at some point.

“The reason why it collapsed when it did, in 1989…is because of that revolution of conscience. So, that made a huge difference. It accelerated the collapse of European Communism, and it brought about its demise without massive bloodshed.”

People tend to forget, he said, that the 20th century’s normal way of affecting massive social change was enormous bloodletting. There was very little of that during the revolution that toppled communism in much of Europe in 1989— only Romania saw widespread violence.

“In every other respect, this great tyranny was dismantled without bloodshed. That’s remarkable, and it might not have happened that way, and it almost certainly would not have happened at that moment in time absent John Paul II.”

Saintly friends

One of John Paul II’s most enduring legacies is the huge number of saints he recognized— he celebrated 147 beatification ceremonies during which he proclaimed 1,338 blesseds, as well as celebrating 51 canonizations for a total of 482 saints.

Mother Teresa of Calcutta is perhaps the most well-known contemporary of John Paul II who is now officially a saint.

Pier Giorgio Frassati, whom John Paul II beatified in 1990, is another well-known holy person that the pope has helped to bring to the world.

Enzler writes in his book that there are several other friends of John Paul who are likely to be saints soon, such as Cardinal Bernadin Gantin, a prelate from Benin who served as Dean of the College of Cardinals— and who confirmed Enzler when he was a child.

Even John Paul’s parents are on their way to sainthood, after Archbishop Marek Jędraszewski of Krakow announced in March 2020 that the archdiocese had opened their beatification processes.

Travels

John Paul II visited some 129 counties during his pontificate— more than any other pope had visited up to that point.

He also created World Youth Days in 1985, and presided over 19 of them as pope.

Weigel says John Paul II understood that the pope must be present to the people of the Church, wherever they are.

“He chose to do it by these extensive travels, which he insisted were not travels, they were pilgrimages,” Wegel said.

“This was the successor of Peter, on pilgrimage to various parts of the world, of the Church. And that’s why these pilgrimages were always built around liturgical events, prayer, adoration of the Holy Eucharist, ecumenical and interreligious gatherings— all of this was part of a pilgrimage experience.”

In the latter half of the 20th century— a time of enormous social change and upheaval— John Paul II’s extensive travels, during which he proclaimed the gospel to huge crowds and made headlines wherever he went, were just what the world needed, Weigel said.

“At a moment in history when the Church really seemed to be on the defensive, when a lot of leaders in the Church seemed to have lost confidence in the ability to proclaim the Gospel, it was very important for this compelling human personality to display how vital and alive the Gospel is in the late 20th century and early 21st. So I think it was a good fit for the time,” he said.

“The saints were normal people”

Like his friend St. Teresa of Calcutta, John Paul II occasionally suffered through periods of darkness and doubt. His private diaries, published in 2014, show him agonizing about whether he was doing enough to serve God.

In addition to spiritual suffering, the pope endured an assination attempt by a Turkish terrorist on May 13, 1981, who shot him in the chest— after which he forgave his attacker, and credited Mary’s intercession for his survival.

He also experienced other health problems in the form of severe Parkinson’s Disease in the last few years of his life.

It is the fact that he was able to overcome the dark periods through prayer that Enzler finds most remarkable.

“He was fearless. He was fearless. And that’s where I think the emulation for me comes,” Enzler said.

“He knew that suffering was mandatory, because suffering belongs to a higher gospel…that’s what he basically showed to me, is that sacrifice and suffering is redemptive.”

Of course, John Paul II is not without critics, and his pontificate not above criticism.

John Paul has often faced criticism for how he handled abusive clergy during his pontificate, with critics pointing especially to the crimes of Marcial Maciel, the now-notorious founder of the Legionaries of Christ religious order. Maciel was only dismissed from ministry after Cardinal Ratzinger became Pope Benedict XVI.

“I think it’s important for people to understand that while this was a man of great spiritual gifts, great intellectual gifts, a luminous personality, a singular capacity for friendship and leadership— this is also a normal human being,” Weigel said.

“He had his dark nights, he had his questions, he had his struggles…and one should not turn him into a plastic car ornament saint. His sanctity is luminous enough coming through this remarkably engaging and attractive human being, that you don’t have to plasticize it.

“Enormous potential for the future”

John Paul II was a scholar who promulgated the Catechism of the Catholic Church in 1992, and also reformed the Eastern and Western Codes of Canon Law during his pontificate.

In addition to many books, John Paul II also authored 14 encyclicals, 15 apostolic exhortations, 11 apostolic constitutions, and 45 apostolic letters.

Enzler recommended picking up the pope’s many writings, such as his 1990 encyclical Ex Corde Ecclesiae. Enzler found that document helpful as he started a classical school with his wife.

“In 27 years of pontificate, for sure he either wrote or talked about many of the topics that we are somehow trying to understand. Let’s just try and find what he said.”

For his part, Weigel says the Church has really only begun to unpack what he calls the “magisterium” of John Paul II, in the form of his writings and his intellectual influence.

In the United States and throughout the world, for example, John Paul’s Theology of the Body remains enormously influential.

“You’ve got an entire generation of Catholics, now in their 30s, 40s and 50s— laity, religious, and clergy, who continue to take their inspiration from John Paul II,” Weigel said.

“So if you subtract him from those biographies, it’s not clear what you get, but it’s clear what you probably wouldn’t get, which is this kind of an evangelical fervor. A lot of the Church would still be stuck in institutional maintenance mode.”

One place that John Paul II’s evangelical fervor has taken root has been in Africa. As mentioned before, John Paul II had a particular friendship with Beninese Cardinal Bernadin Gantin, and visited Africa many times.

“John Paul II was fascinated by Africa; he saw African Christianity as living, a kind of new testament experience of the freshness of the Gospel, and he was very eager to support that, and lift it up,” he said.

“It was very interesting that during the two synods on marriage and the family in 2014 and 2015, some of the strongest defenses of the Church’s classic understanding of marriage and family came from African bishops. Some of whom are first, second generation Christians, deeply formed in the image of John Paul II, whom they regard as a model bishop.”

“I think wherever you look around the world Church, the living parts of the Church are those that have accepted the Magisterium of John Paul II and Benedict XVI as the authentic interpretation of Vatican II. And the dying parts of the Church, the moribund parts of the Church are those parts that have ignored that Magisterium.”