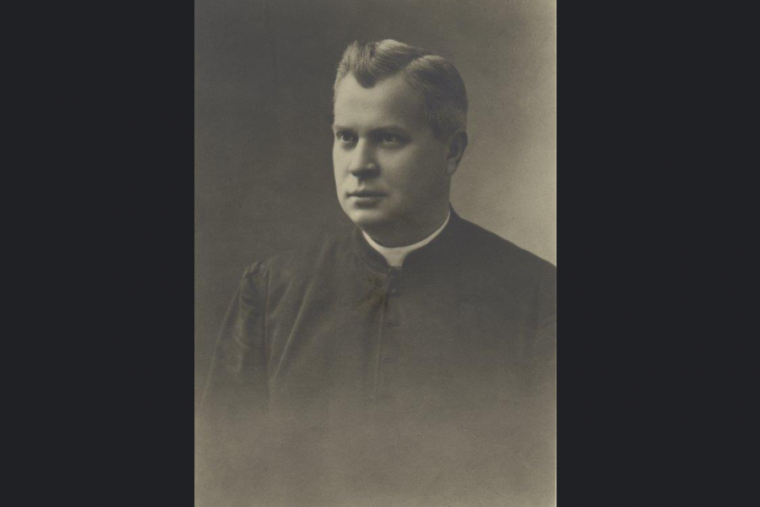

Fr. Marceli Godlewski. Credit: Franciscan Sisters of the Family of Mary, Warsaw.

All Saints Church in Warsaw is an imposing edifice. Its soaring twin bell towers were inspired by a Renaissance abbey in Italy. In 2017, it became the first building in Poland to be designated a “House of Life.”

The title was awarded by the International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation, named after the Swedish diplomat who saved tens of thousands of Jews in Nazi-occupied Hungary.

At a ceremony marking the designation, Samuel Tenembaum, the son of the foundation’s founder, declared: “This was a place of life, a fortress of life; life had its headquarters here within the walls of this church, and the darkness could not overcome it.”

The church on Grzybowski Square earned this distinction thanks to the actions of Fr. Marceli Godlewski, its pastor during the Second World War, and those who served alongside him.

Before the Nazi invasion of Poland, Godlewski would have seemed an unlikely candidate to be honoured as “Righteous Among the Nations.” His citation on the Yad Vashem website describes him as being “vocally anti-Semitic most of his life.”

He took charge of the downtown parish in 1915 and was of advanced age when the Nazi occupation began in 1939.

A year before the occupiers arrived, around 370,000 Jews were living in the Polish capital, comprising almost 30% of the population. They formed the largest Jewish community in Europe.

The Nazis ordered the city’s Jewish population to move to a district that was just 1.3 square miles in size. They separated the so-called Warsaw Ghetto from the “Aryan” side of the capital in November 1940.

Godlewski’s parish was now located inside the ghetto, where overcrowding, meagre rations, and Nazi oppression quickly took their toll.

The priest busied himself serving an estimated 2,000 Catholics of Jewish origin. But he realized that, in conscience, he had to do more. He obtained his bishop’s permission to minister more widely.

Together with another priest, Fr. Antoni Czarnecki, he housed 100 Jewish people in the church’s presbytery. The parish’s communal kitchen fed around the same number. Everyone was entitled to help, regardless of whether they were baptized.

To help as many people as possible, the parish had to rely on subterfuge: providing hundreds of false baptismal certificates to the presbytery’s residents, children, and those seeking to escape the ghetto.

As Czarnecki later explained, “To make the certificate, it was necessary to search through the death register for a death certificate, most often of a child or infant, whose year of birth coincided with that of the person wanting to ‘break out’ of the ghetto.”

The ghetto resident then received a baptismal certificate bearing the name, date of birth, and date of baptism of their “double” as recorded in the parish’s baptismal register.

“I have personally known many of them and, to this day, they still use the assumed surname,” Czarnecki recalled after the war.

If the Nazis had discovered this ruse, Godlewski and Czarnecki would have faced the death penalty. In 1941, Hans Frank, governor-general of the occupied Polish territories, decreed that Jews who left their designated area would be executed. Those who sheltered them would face the same punishment.

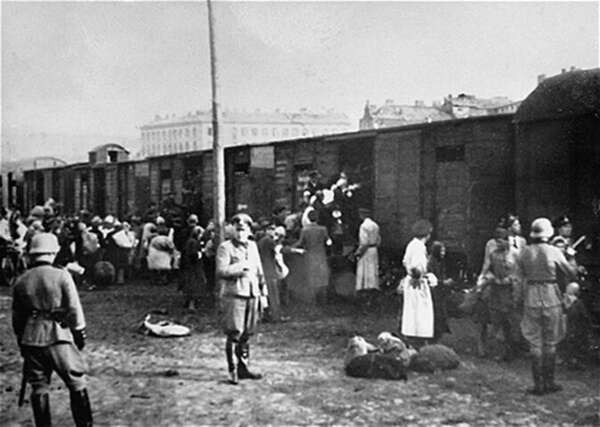

Godlewski and Czarnecki were obliged to leave the ghetto in July 1942, the same month that the Nazis launched the “Grossaktion Warschau” (pictured below), in which more than a quarter of a million Jews were deported and murdered at the Treblinka extermination camp.

Following an uprising which lasted nearly a month, the Nazis liquidated the ghetto in the spring of 1943. General Jürgen Stroop, who oversaw the suppression of the revolt, sent a triumphant report to SS chief Heinrich Himmler entitled “The Jewish Quarter of Warsaw Is No More!”

Estimates vary for how many people Godlewski saved, from 1,000 to as many as 3,000. The priest died at his home near Warsaw on Christmas Day, 1945.

Ludwik Hirszfeld, a pioneering scientist who was jointly responsible for naming the blood groups A, B, AB, and O, credited Godlewski with helping him to survive the Holocaust.

“When I recall his name, I am overcome by emotion,” he wrote. “Passion and love within one soul. Once a militant anti-Semite, a priest fighting with his words and writings. But when fate made him see people living in extreme poverty, he rejected his former attitude and devoted his whole passion to Jews.”

The Polish bishops’ conference highlighted Godlewski’s life on International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

In a statement marking the day, bishops’ conference president Archbishop Stanisław Gądecki noted that 27 January is the 76th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz.

The official Auschwitz Memorial commemoration event, held online due to the pandemic, focused on the more than 200,000 children murdered in the concentration camp.

The commemoration included prayers by the Chief Rabbi of Poland Michael Schudrich, Catholic Bishop Roman Pindel, Orthodox Bishop Atanazy and Evangelical-Augsburg Bishop Adrian Korczago.

Gądecki said: “This anniversary obliges us to loudly express opposition to all manifestations that trample human dignity: racism, xenophobia, and anti-Semitism. On this anniversary, we appeal to the modern world for reconciliation and peace, for respect for the right of every nation to exist and to freedom, independence, and the preservation of its own culture.”

“Let us pray for the victims of World War II. Let us also pray that, in each person, love for one’s neighbour may always be victorious!”

Source: CNA