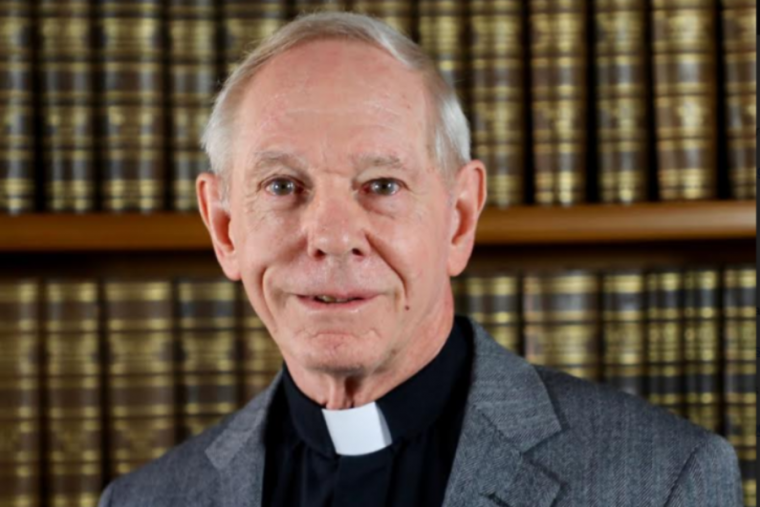

Research astronomer Fr. Christopher Corbally. Courtesy of Fr. Corbally

Somewhere between Mars and Jupiter there is a hunk of rock that now bears the name of a living English Catholic priest.

Fr. Christopher Corbally said Wednesday that he was “thoroughly surprised” when he heard asteroid 119248 had been named in his honour earlier this month.

“I’m not an asteroid person, I’m a star person,” Fr Corbally states.

The 74-year-old is credited with advancing our understanding of multiple stellar systems, stellar spectral classification, galactic structure, star formation, and telescope technology. But during his distinguished career, he hasn’t focused on asteroids.

According to NASA, asteroids “are rocky, airless remnants left over from the early formation of our solar system about 4.6 billion years ago.” The current number of identified asteroids is 958,915, ranging in size from less than 33 feet to 329 miles in diameter.

The International Astronomical Union (IAU) has strict rules for the naming of minor planets, as asteroids are also known. According to its website, they must be 16 characters or less, ideally one word, pronounceable, non-offensive, and substantially different to previous names.

Asteroids cannot be named after politicians or military figures until a century after their deaths, or after commercial ventures. Pet names are also discouraged.

Asteroid 119248 Corbally was discovered by the American astronomer Roy Tucker on September 10, 2001 at the Goodricke-Pigott Observatory in Tucson, Arizona. Tucker recently retired as a senior engineer in the Imaging Technology Laboratory of the University of Arizona.

Corbally, a UA Associate, used Tucker’s electronic cameras for observations of spectra at Kitt Peak, southwest of Tucson, and with the Vatican Advanced Technology Telescope (VATT) on Mount Graham in southeast Arizona. He has also worked in recent years with Tucker on a project examining celestial objects that vary in brightness.

Corbally joined the Vatican Observatory’s staff in 1983 as a research astronomer, serving as vice director for the Vatican Observatory Research Group in Tucson until 2012.

Asked what he knew about the asteroid that had been named after him, he said: “Very little. It’s about a mile or so in diameter, so it’s a small body. It’s in the middle range of brightness. It’s not the very faintest. It’s not the very brightest.”

Corbally, a member of the Society of Jesus who was ordained in 1976, noted he was the 16th Jesuit to lend his name to a minor planet. Others include founder St. Ignatius (1491-1556), Argentine astronomer Buenaventura Suárez (1678-1750), and Johann Grueber (1623-1680), an Austrian missionary to China.

Speaking of asteroid 119248, Corbally said: “It’s like the others: a little bit eccentric. I don’t know whether that applies to Jesuits on the whole…”

“It’s orbiting in the space between Jupiter and Mars. It’s called the Main Asteroid Belt. This collection of asteroids all have this orbit that is not as circular as the Earth’s is around the sun. So they’re what we call slightly eccentric.”

He continued: “There’s a whole hive of these asteroids out there. They are part of the leftovers from the formation of the sun and our major planets that we have — Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars — and then the giant planets, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune.”

Corbally, who was born in London, became interested in astronomy when he was sent to school at Stonyhurst College in Lancashire in northwest England.

“That was out in the country,” he recalled. “The dark sky was available. That was when you could actually see the sky, not the clouds. It would be clear and the stars were wonderful.”

He said that his mother would mail him newspaper articles about the night sky and he would stargaze using his naked eye because the school’s telescope was out of commission.

Corbally, who is still based in Arizona, said his asteroid was likely to exist long after everyone on Earth today had passed away.

“Unless it gets perturbed in its orbit, which can always happen — Jupiter is the great perturber around there — or, I suppose, if it crashes into another asteroid,” he said.

“But there’s so much space out there. You get millions of asteroids happily wandering around there. We don’t realise how much space there is.”