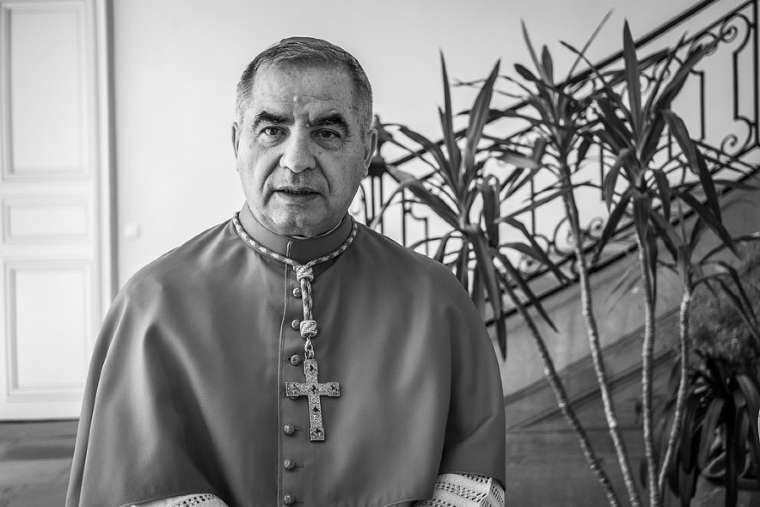

Cardinal Angelo Becciu. Credit: Credit: Claude Truong-Ngoc / Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

At around 6pm on Thursday, Pope Francis summoned Cardinal Angelo Becciu to a meeting, multiple sources tell CNA. In the hour before, the pope reportedly had been given an advance copy of a forthcoming news report on Becciu, his stewardship of Vatican finances, and new allegations that he used his position, and Church funds, to enrich his family.

Within an hour, the Holy See press office released a statement saying that the pope had “accepted Becciu’s resignation” from his role as head of the Congregation for the Causes of Saint and his rights as a cardinal. Becciu, by all accounts, had not even made it back to his nearby, recently renovated extensively, apartment in the Palazzo del Sant’Uffizio before the news was released.

Sudden “resignations” of this kind are not unknown at the Vatican – and Becciu himself has often been on the other side of the table, allegedly forcing, for example, the “resignation” of the Vatican’s first Auditor General, Libero Milone who was accused of “spying” on Becciu’s personal finances.

Like Milone, Becciu has since insisted that he did nothing wrong. Unlike Milone, who said Becciu threatened him with criminal prosecution if he did not leave his office quietly, the cardinal’s resignation marks a new beginning, rather than an end to his story.

After the news broke Thursday evening, multiple Vatican sources told CNA that both Vatican prosecutors and the Italian Guardia di Finanza are expected to lay criminal charges against Becciu. “I am innocent and I will prove it,” Becciu told an Italian newspaper Friday morning. The odds seem good that he will be given his day in court to make the attempt.

Becciu’s fall comes after nearly two years of reporting placing him at the center of several different, overlapping Vatican financial scandals.

Before his role at the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, Becciu served as the sostituto at the Secretariat of State, operating as a kind of papal chief-of-staff and de facto manager of the daily operations of the curia’s most powerful department.

Under his stewardship, the secretariat engaged in a number of highly speculative financial ventures, including dealings with Swiss banks known for their lax approach to money laundering, and Becciu was alleged to be personally responsible for stymieing a number of attempts at financial transparency and reform.

The former head of the Vatican Secretariat for the Economy, Cardinal George Pell, frequently found his efforts thwarted by Becciu. A source told CNA that one occasion Becciu gave Pell – his superior – a formal “reprimand” for his attempts to bring transparency to the Secretariat of State. On another occasion, Becciu countermanded an audit of all Vatican finances ordered by Pell.

Since his vindication on sex abuse charges by the Australian High Court, Cardinal Pell had not commented on his former role or the various financial scandals which have led to from and through Becciu’s office.

But after Thursday’s announcement that Becciu had “resigned” Pell issued a rare public statement, congratulating Pope Francis on what was, in fact, a summary sacking.

“The Holy Father was elected to clean up Vatican finances,” Pell said. “He plays a long game and is to be thanked and congratulated on recent developments.”

At the time of his election, Pope Francis was, indeed, widely hailed as a new broom that would sweep clean curial corruption. Since then, many have grown frustrated at the apparent lack of progress and the appointment, disappointment, and departure of reformers like Milone and Pell.

But while the Holy See has not officially acknowledged the reasons for Becciu’s departure, he has now become the first curial cardinal, at least in the modern era, to be dismissed for financial misconduct – something few would have predicted when Francis was elected in 2913.

While Becciu’s dismissal has taken many in the media by surprise, the drumbeat of reports in recent years has indicated that Vatican prosecutors were – at last – being given a free hand to pursue their work wherever it led.

In October 2019, several of Becciu’s former employees and closest collaborators at the Secretariat of State were the subject of a raid by investigators. By February, Becciu’s former deputy and effective right hand man, who had moved on to a position at the Vatican’s supreme court, was raided and suspended.

The arrest of Gianluigi Torzi, a key player in the London property deal that triggered the initial investigation into Becciu’s old department, was a major sign prosecutors were intent on bringing charges, not just filing reports.

Perhaps the most significant development came in July when a search and seizure warrant was served on Italian businessman Rafaelle Mincione in a Roman hotel. That warrant was sought by Vatican prosecutors, but it was issued by an Italian magistrate and served by Italian state police, indicating that the investigation was sufficiently developed to convince Italian authorities to intervene.

But after generational attempts to bring order to Vatican finances, what makes this attempt different?

In addition to the spotlight which has fallen on Becciu and his collaborators over the last year, Vatican prosecutors have also had the unfortunate benefit of an acute cash crunch developing for the Holy See, exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic. Bluntly put: When there is less money around, it is harder to hide what is missing.

At the same time, Moneyval, the EU Commission’s anti-money laundering watchdog, has made repeated inspections of the Vatican’s financial institutions – with another progress report due out in the next few months. While they have expressed satisfaction with some of the financial structural reforms brought in under Pope Francis, they have repeatedly noted the Vatican’s poor record of prosecuting criminal financial behaviour, increasing the pressure on investigators to bring charges.

This pressure will have increased exponentially if Italian prosecutors plan to bring charges of their own: the Vatican simply cannot risk appearing to have shied away from bringing a case if the Italian courts get involved.

Becciu has insisted on his innocence and demanded he be given the opportunity to prove it. Lucky for him, in this case, his desire may well align perfectly with those of the Vatican prosecutors and financial inspectors. A public trial of curial officials, headlined by a cardinal, may be the last thing many in the Vatican wanted or expected to see. But it may now become the next stage of a story that still has a long way to go.

Source: CNA