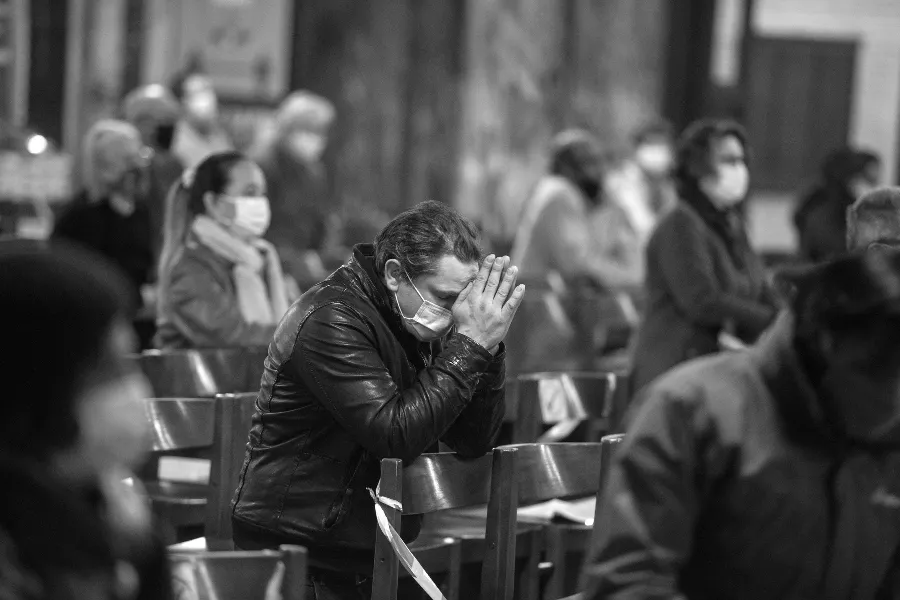

Mazur/cbcew.org.uk.

Today was supposed to be England’s “Freedom Day.” Back in February, Prime Minister Boris Johnson told a weary populace that, all being well, the country could look forward to the end of a nationwide lockdown on June 21.

But all wasn’t well. With a third wave of COVID-19 spreading across the country, Johnson announced that the easing of restrictions in England would be delayed to July 19.

But with “Freedom Day” tantalizingly in sight, CNA spoke with priests across England about the pandemic’s long-term impact on their parishes.

The conversations revealed that the coronavirus had not only hit parishes hard, but also exacted a deep toll on priests.

Parishioners lost

All of the priests acknowledged that a significant number of parishioners had vanished during the crisis — and were unlikely to return.

Fr. Alexander Lucie-Smith, Parish Priest of St. Peter’s, Hove, a seaside town in East Sussex, said that numbers were now about 60% of what they were before the pandemic, though giving was at around 70%.

He said: “The money situation is not as catastrophic as we thought it was because the people who disappeared tend to be those who were least committed and giving least money. They also tend to be the young.”

He explained that some young families were wary of bringing their boisterous children to Mass at a time of tight sanitary regulations.

“It’s not just in this parish, but in many parishes, this is the case,” he said. “This is going to have a knock-on effect also on the Catholic schools. Many of the Catholic schools are Catholic in name only. They’ve got declining numbers of Catholics in them. And I think that will carry on.”

“What’s going to happen in five, 10, 20 years’ time is that a lot of churches are going to close, simply because the money is not there to maintain these very expensive buildings.”

Conscious of the need to reconnect with parishioners, Fr Lucie-Smith has visited local Catholic schools every week to talk to students and parents. His parish is also hosting a number of social events over the summer, including concerts and an initiative modelled on the Courtyard of the Gentiles.

Fr. Alexander Sherbrooke, Parish Priest of St. Patrick’s, Soho, said the pandemic’s impact was so profound that it was possible to speak of “a pre-COVID and a post-COVID Church.”

Throughout the crisis, his parish in London’s West End has engaged in a remarkable outreach to the local homeless population, offering not only food, but also adoration, access to sacraments, and the rosary.

“The pandemic has obviously been a time of purification,” he said. “Certain people have fallen by the wayside. Others have remained faithful. But those who have remained faithful have really drilled down in their faith in certain key areas.”

“First of all, our volunteers — there are a good 150 of them — have developed a deep personal relationship with the poor. And so there’s a real sense of community, of mutual belonging.”

“Secondly, there’s a much deeper desire for a proper celebration of Mass, a deeper desire for adoration, more solemnity in the sacramental life. In other words, in the world of moving boundaries and lack of certainty, the liturgy, the Mass, adoration, is something which is ever more important.”

“And I think also what’s important to them is doctrinal clarity. If I’m going to be a Catholic now, post-COVID, I’ve got to be sure what I’m about, what I believe in, and how to articulate that.”

Fr. Rick McGrath, the Parish Priest of St. Wilfrid’s, Burgess Hill, in the county of West Sussex, said that attendance was now up to “COVID capacity.”

Under current guidelines, all churches in England have a reduced capacity due to the requirement for “social distancing.” Some parishes have fewer Masses than before and require parishioners to book online.

McGrath, a 76-year-old Minnesota native, said that in addition to those who no longer attend Mass, there is a group of Catholics who watch the livestream but do not physically attend church.

He said that while he did not see this as ideal, it was “better than nothing if you’re housebound.”

In Fr. Stephen Pritchard’s parish, Our Lady of the Assumption, Gateacre, a suburb of Liverpool, a team has made hundreds of phone calls to parishioners throughout the pandemic. Despite these efforts to reach out, the parish has lost about 25% of Mass-goers.

“We’re trying to connect with a group of 100 people to see what situation they’re in, individually,” he said.

“They’ve all got different scenarios in their lives. So we have a group of people working on that now, ringing all those people up.”

“I think that for some Catholics this is the exit moment and they will have disaffiliated,” he said, stressing that it is vital for the Church to “know who people are” and not “break the thread with people.”

“The local and the personal are really significant,” he said. “But also, I think there’s an opportunity here for the whole Church in the country to look again at ‘What does the Eucharist mean?’”

“The Eucharist is indispensable, irreplaceable, and of highest worth to Catholics. So what does that really mean for us now, especially those people who maybe ‘watch Mass’ on a Sunday in their pyjamas having a cup of tea. What does it mean to be a Eucharistic community?”

He referred to a message called “The Day of the Lord,” issued by the bishops of England and Wales in April. The bishops appealed for Sunday Mass to be restored “to its rightful centrality,” after Catholics were dispensed from the obligation to attend at the start of the pandemic.

“It was good that the bishops signalled the importance of the Eucharist in the lives of Catholics,” Pritchard said. “I felt encouraged by what the bishops said.”

“I think we need more of a dialogue, nationally, to talk about what is the significance of the Eucharist for us as Catholics today.”

Other priests said that they had felt disconnected from the Church’s national leadership during the crisis and wanted more guidance on how to rebuild their parishes after the pandemic.

Turning outwards

Pritchard noted a new desire among his parishioners to go out and serve the wider community.

“There’s been a real sense of a willingness to reengage with our local community in a way that we haven’t done as much before,” he said.

“There’s always been an outward focus but it’s really been made real in the last 14 months.”

While Mass numbers have dropped, the collection has increased. The parish has supported an initiative that feeds 700 local people a week. Donations to the food bank have risen fourfold.

“How the parish rallied around and contributed to that I think was amazing,” he said.

McGrath, who is responsible for several churches, said that he had noticed a similar phenomenon in his parish.

“We’ve had a fair number of elderly parishioners who aren’t on email or the internet. We’ve got people who come every Friday afternoon and pick up stacks of newsletters and deliver them — food banks, shopping for people, all of that. It’s been terrific,” he said.

Moving online

Lucie-Smith said that livestreamed Masses and online sacramental courses were likely to continue after the pandemic. But he felt they were a poor substitute for face-to-face encounters.

Pritchard agreed that the “hybrid model” of sacramental preparation would endure, with a mixture of online and in-person meetings.

“We have been doing our baptism preparation via Zoom and that’s been quite successful. There have been good benefits. Part of it, I think, we would keep hybrid,” he said.

Sherbrooke is committed to livestreaming Sunday Mass for as long as necessary. He suggested that livestreamed Eucharistic adoration, in particular, was valuable as viewers could share their prayer requests online while it was taking place.

McGrath, a self-declared “technophobe,” praised parents in his parish who have helped to prepare children for their First Communion via the internet.

But he said he hoped that online meetings would not be the norm after the pandemic.

“I admit I’m speaking from an old age and I’m not very good on technology, but I just don’t see how the Church can exist without that sense of community — real, living community,” he commented.

Burning out

Lucie-Smith, a seemingly eternally youthful priest, said that the pandemic had drained him of energy.

“There was a headline in the paper I saw that said that people who worked throughout the pandemic are now burnt out. I think that applies to a lot of clergy,” he said.

“I really do feel that I am completely burnt out.”

Sherbrooke suggested that priests have been affected by the pervasive sense of loneliness associated with lockdown.

“I think that because the priest by definition needs people around him, when those people have been taken away, there’s a real sense of loss. I think that’s been terrible for priests and some will have fallen by the wayside,” he said.

Pritchard observed that priests have had to cope with constant change throughout the pandemic. They have had to master complex, ever-evolving regulations to prevent the spread of the virus, while overcoming new obstacles to serve their parishioners.

“I think that priests have been incredibly resourceful, have dug deep to lead in new ways. Many have had to upskill in innumerable ways. Having to adapt to constant changes has been wearisome,” he said.

“The first lockdown for me was not only looking after funerals in my own churches but two other churches where the priest was shielding. So much death and only relating to people remotely was very challenging. We need to care for priests as many are not too good at sharing their needs with others.”

Another pastor mentioned that he had heard of two priests committing suicide in the past 12 months. He did not know if the cases were related to COVID-19, but speculated that the pandemic might have been a factor.

In contrast, McGrath noted that some priests were thriving amid the pandemic.

“Like the general population, it is my impression that some priests have suffered some anxiety during all this, but those in my area, or that I am in contact with, seem to have done very well: following the rules and guidelines, but not slavishly, and reintroducing Masses and baptisms as soon as possible,” he said.

“One friend of mine, still working despite long-term cancer, has actually blossomed in all this. Because of his health, he had reduced his weekday Masses, but he reinstated daily Mass and still does three weekend ones, and rising to the challenge also of livestreaming, spends a great deal of time preparing superb homilies every day.”

“I can’t speak for everyone, and I do know of at least one priest (fairly newly ordained) who is off with depression. But overall it seems to me that most have done their best and that has been pretty good.”

Currently, it’s not possible to quantify the number of priests in England suffering from pandemic burnout. The priests CNA spoke with may be unrepresentative. But their comments suggest that, as “Freedom Day” approaches, the deeper impact of the coronavirus crisis on the Church may only just be coming to light.

Source: CNA