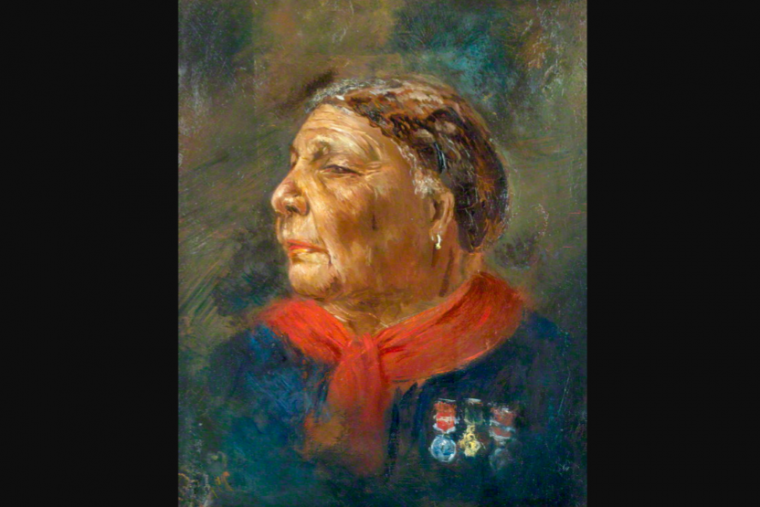

Photo of a portrait of Mary Seacole (c.1869), by Albert Charles Challen (original held by the National Portrait Gallery in London.) Public domain.

She was voted the “greatest Black Briton.” A statue of her stands opposite the Houses of Parliament. Her heroic life is taught to students in England as part of the National Curriculum. Yet few people know that Mary Seacole was a Catholic convert.

There may be a good reason for that: although the 19th-century businesswoman who cared for wounded British soldiers during the Crimean War is a celebrated figure today, little is known about her journey to Catholicism.

Jane Robinson, author of a 2004 biography of Seacole, told CNA: “I was unable to find out much about Mary’s Catholic faith myself, but given that she was a convert, I can only assume that it meant a great deal to her.”

“It’s frustrating that in this, as in many areas of her personal life, information is scant. She obviously considered it to be a private affair.”

Seacole was born in 1805 in Kingston, Jamaica. Her father was a Scottish lieutenant in the British Army and her mother was a Jamaican “doctress” who taught her how to treat illnesses using herbal remedies.

She traveled to Britain in the 1820s, and worked as a nurse in the Caribbean and in Central America. She treated patients suffering in the cholera epidemic of the time.

When the Crimean War broke out in 1853, Seacole tried to join a contingent of nurses but was refused. She decided to travel independently to set up an establishment called the “British Hotel,” offering “a mess-table and comfortable quarters for sick and convalescent officers.”

Catholic author and broadcaster Joanna Bogle told CNA: “Mary Seacole never sought to be a nurse — she was a well-to-do business lady who ran a shop selling snacks and sweets to the officers.”

“She was certainly kind and helped sick soldiers, offering them comfort and doing what she could for them, and sometimes offered some of her family remedies, learned from her mother and grandmother in Jamaica.”

“Above all, she offered the strength of her faith, and the warmth of her heart: there are touching accounts of her holding dying soldiers, and saying ‘Mother is here…’ She became known affectionately as ‘Mother Seacole’ and years later, living in London, would recall with tears the poor dying soldiers whose last hours she had shared.”

When the war ended in 1856, Seacole returned to England with little money and in poor health. Prominent supporters, including the Duke of Wellington and William Howard Russell, war correspondent of the London Times, raised funds on her behalf.

Fr. Stewart Foster, the archivist of the Diocese of Brentwood in southeast England, told CNA that Seacole was received into the Church in 1860, at the age of 55. It appears that she became a Catholic in England, but because her reception occurred after the publication of her autobiography she left no record of her reasons for embracing the Catholic faith, which was remerging in Britain after centuries of suppression.

When Seacole died in 1881, she was buried in St Mary’s Catholic Cemetery in Kensal Green, northwest London. Her gravestone, which was restored by the Jamaican Nurses Association in 1973, describes her as “A notable nurse who cared for the sick and wounded in the West Indies, Panama and on the battlefields of the Crimea.”

The restoration of her grave was part of a wider rediscovery of her life, which had been all but forgotten in the decades after her death.

In 2004, Seacole came top of a list of 100 great Black Britons. The poll took place after a BBC series asked viewers to vote for the “100 Greatest Britons,” but no Black people were included in the top 100.

Following the poll, Seacole was the subject of a television documentary, several biographies, and an exhibition at the Florence Nightingale Museum. A portrait was discovered and placed in the National Portrait Gallery in London.

A statue of Seacole was erected in the grounds of St Thomas’ Hospital, London, in 2016. The statue, which faces the Palace of Westminster, was believed to be the first of a Black woman identified by name in Britain.

Reflecting on Seacole’s selfless service during the Crimean War, Bogle said: “I remember reading that when men are dying they often call for their mothers. It is apparently something noted by many nurses over the years.”

“I am rather moved by the thought of kindly Mother Seacole responding to the cry of a dying soldier, so that at least he felt loved and caressed… and perhaps somewhere in all of that is the thought that surely Our Lady heard their cries.”