Cardinal Vincent Nichols at Westminster Cathedral, London, on June 9, 2020. Credits: Mazur/cbcew.org.uk.

On the eve of his 75th birthday, Cardinal Vincent Nichols cast his mind back to the day he was installed as the archbishop of Westminster.

“I was told — and you know, when you’re a bishop you do what you told — ‘kneel here at the threshold of the cathedral and pray before you enter.’ And that struck me very forcefully, that the threshold is a very important place,” he recalled.

“And for people coming to church, or people approaching the church, crossing the threshold was a huge, sensitive, and sometimes very difficult action. We trip in and out because we’re too familiar with it all. But for somebody who has been away a long time or somebody who’s exploring faith, crossing the threshold is a huge step.”

“So I kept thinking we must find ways of making that journey easier.”

Cardinal Nichols said that from that day in May 2009 onward he tried to build on existing parish programs to help more people enter the Catholic Church.

“It’s to ease the passage to the meeting with Jesus. That’s what we’re called to do,” he said. “We’re called to say to people: ‘Come and meet Him. I’ll bring you.’ And they’re very hesitant, very shy, and very uncertain. But that’s the essence of evangelization.”

The cardinal’s birthday, on 8 November, falls during England’s second nationwide lockdown. That rules out any public celebration. He is likely to mark the occasion with a cake in the presence of others in his “bubble.” He is also expected to tender his resignation as archbishop of Westminster, as bishops are required to do when they turn 75.

He will reach this milestone at a challenging time for the Catholic Church. Two days after his birthday, the UK.’s Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA) is expected to issue its final report on the Church in England and Wales. Previous IICSA reports have criticized Benedictine-run schools and the archdiocese of Birmingham, where Cardinal Nichols served from 2000 until his appointment to Westminster.

The cardinal spoke to CNA shortly before the government suspended public Masses in England for the second time this year because of rising coronavirus cases. He has led a spirited attempt to persuade Prime Minister Boris Johnson to reverse the decision.

His remaining time as archbishop of Westminster is likely to be overshadowed by the pandemic and its aftermath.

“It’s a crisis, and a crisis is a crossroads,” the cardinal said, speaking via Zoom from Archbishop’s House, Westminster, in central London. “And a crisis is a challenge, and I do believe that if you get into a challenge in the right way then you’ll come out of it stronger. It will be also a conversion.”

“What have we learned? We’ve learned that we are not self-sufficient. We have learned that we’re all in the same boat. We have learned that, whether you live in a gated housing estate or on a council estate, this virus finds its way to you. And in that sense, it teaches us interdependence and humility.”

Nichols said that one of the worst aspects of the crisis was that friends and relatives were “cruelly separated” from ill loved ones.

“It’s just awful,” he said. “A friend of mine is in a nursing home, and all we’ve been able to do is to park in the car park of the nursing home and talk to her via a mobile phone — she being in an upstairs window. And, you know, that’s very, very painful. Very painful.”

The president of the Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales recognises that the virus is likely to have far-reaching consequences for the Church.

“There’s no doubt there are changes,” he said. “Some of them have risk to them. I think many people really appreciate being able to share in the Mass through livestreaming. But we always have to remember that the Eucharist is not a service provided by the clergy.”

“The Eucharist is the life of the Church and it’s the Church that makes the Eucharist, not simply a priest in a church building. And so the Eucharistic heartbeat, or pulse, of the Church is not fully expressed on the internet.”

“And I have no doubt that, in their heart of hearts, Catholics really want to get back to Mass, which is why this present moment is so full of anguish, that we’re going to be excluded from that again for a short while.”

Nichols told contrasting stories about how Catholics were adapting to the suspension of public worship. In one London parish, a woman told her priest that she loved internet Masses “because I can sit on our balcony and have a cup of coffee.”

“And then from the neighboring parish,” the cardinal said, “the parish priest tells me: ‘We have a lady in the parish who is 103 and for many years she has not been able to get to Mass. But now she can join in the Mass on the internet.’ He says she gets up every Sunday morning and she gets dressed in her best clothes, and she puts her hat on and she comes before the television set and goes to Mass.”

Nichols suggested that the lockdown had opened up new possibilities for communicating the Gospel, catechesis, and studying the Scriptures.

“But we do need to gather,” he stressed. “This sacramental life of the Church is corporal. It’s tangible. It’s in the substance of the sacrament and of the gathered body … I hope that this time, for many people, of Eucharistic fast gives us an additional, sharpened taste for the real Body and Blood of the Lord.”

Nichols said that the pandemic had helped him, as the archbishop of a sprawling diocese, to appreciate the importance of “local energies.” He praised the “ingenuity” of Westminster priests.

“I would like to think that in this period we’ve become much less top-down and much more enhancing and supporting local initiatives,” he said.

He is proud of the charitable work across the diocese, led by the energetic Caritas Westminster. He mentioned one parish that was supporting 15 families at the start of the first lockdown in March and is now helping 75. Another parish had increased its food distribution by 400% in the same period.

Cardinal Nichols was born in 1945 in Crosby, Lancashire, in northwest England. The Catholicism of his childhood was starkly different from that of today.

“For example, when I was a young boy, we would never go near an Anglican church,” he recollected. “We wouldn’t even go into the churchyard, nevermind join in prayers. That was enemy territory.”

As a young priest in Liverpool, he would be accompanied by two men as he took Holy Communion to the sick, in case of possible harassment on the street.

“I’ve gone from that to the situation where we are now, where we see ourselves with other Christian bodies in very close cooperation, in a very shared witness. And it’s broadened out to the presence and the partnership with leaders of other faiths as well,” he said.

One of his most cherished memories as archbishop is accompanying four Muslim leaders — two Shiite and two Sunni — to a meeting with Pope Francis in 2017.

“It was very interesting that, as the photographs were lined up, the former Muslim men wanted to be mixed. So they didn’t want two Shia Muslims on one side and two Sunnis on the other. They wanted to show that this was not just a meeting between Christians and Muslims, but between the different Muslim families,” he remembered.

Cardinal Nichols said that within his lifetime he had seen Catholics in England shake off the legacy of persecution and reclaim a fitting place in public life. At the same time, he noted that the Church’s demographics had changed dramatically, with English and Irish Catholics joined by sizable numbers from Poland, India, Africa, the Philippines, and elsewhere.

“Churches are vibrant. They’re full of very many different cultural characteristics and cultural expressions of faith,” he said. “And I honestly think they probably have deeper, more divergent spiritual roots than when I was a boy. Our way of faith was very much the faith of the Church and the ways of expression of the Church.”

“Now, I think, Catholics are much more at ease in a deeply personal relationship with the Lord, in a spirituality that is more personally rooted. And the societies and the fabric of the Catholic Church is much looser and more diverse than it used to be. And in many ways, it’s more biblical, it’s more personal, it’s more spiritual than it was when I was a boy.”

Nevertheless, the Church has had to continue to fight to be understood in the corridors of power.

“The Catholic Church’s relationship with the political world has changed a lot in my time,” he reflected. “I think to begin with we were pretty much on the fringe. Then, with the growing impact of the quality of Catholic education, political leaders and figures who were Catholics began to emerge and take prominent roles. And that helped to make a kind of almost structured dialogue between politics and the Catholic Church have a bit more substance to it.”

He cited the example of Cardinal Basil Hume, who served as archbishop of Westminster from 1976 to 1999. Hume was invited to become a member of the House of Lords, the second chamber of the UK Parliament. He declined the offer because it was intended for him personally, rather than extended to the archbishop of Westminster.

“I think the situation’s changed quite a lot since then,” Nichols said. “The patterns of political influence have become much more dispersed. And the skills of political lobbying are probably not the strongest among us. They are stronger in other lobby groups. And politics, I believe, is much more fragmented now.”

He continued: “Party loyalty is not what it was. It’s much more interest groups and pressure groups. And in that mix, we are not particularly skilled or particularly well-represented. We have our clear lines of major interest. So we are a major partner in the provision of education. And we have a major role, I think, in overseas aid, and in some international issues. But in the day-to-day mix of politics, it’s much more closed, much more blind to the importance of the religious insight and faith.”

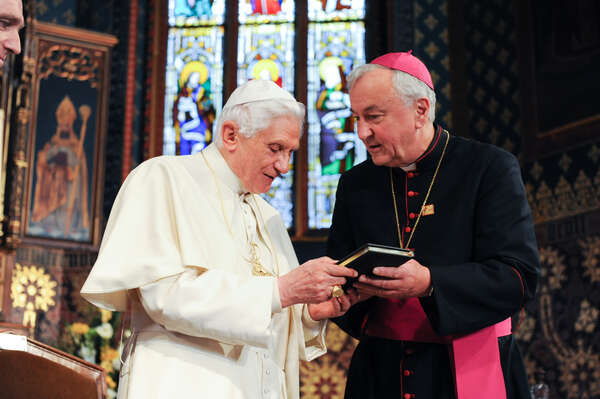

The cardinal said that the celebrated address delivered by Benedict XVI at Westminster Hall during his 2010 papal visit to Britain remained “very true.”

“His appeal was that the world of secular thinking, the world of secular politics, needs to be in a thoroughgoing dialogue with the world of religious belief,” Cardinal Nichols recalled.

“And he said it’s reason that bridges these. So, the world of secular reasoning can benefit from the insights of faith, and the world of faith benefits from the rigors of reasoned argument to protect it from extremism and fundamentalisms.”

“That appeal to a systematic dialogue is something that we work on. But that area has not got any easier in the last 10 years.”

Source: CNA